After months of negotiations, more precisely since the launch of the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum (LPDF) last November, Libya has a new government. The executive, led by Abdul Hamid Ddeibah, has obtained the confidence of the House of Representatives meeting in Sirte: 132 votes in favour, just one against. He and President Mohammed Al Manfi, who was elected on 6 February by the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum, have the task of guiding the country towards the next elections in December, which Ddeibah has pledged not to run. The government will be composed of 27 ministers, 6 undersecretaries of state and 2 deputy prime ministers.

A silver lining

The news of the birth of the new executive assumes great significance when one considers that the government that has so far led the country, chaired by Fayez Al Sarraj, has never obtained the confidence of the House of Representatives, the legislative body elected after the 2014 electoral round and installed in the east of the country, in Tobruck.

Parliament, in fact, systematically denied confidence to the executive stationed in Tripoli after the signing of the Skhirat agreements in December 2015, which in fact would have limited the power and autonomy of Marshal Khalifa Haftar, entrusting the command of the armed forces to the Presidential Council (art.8).

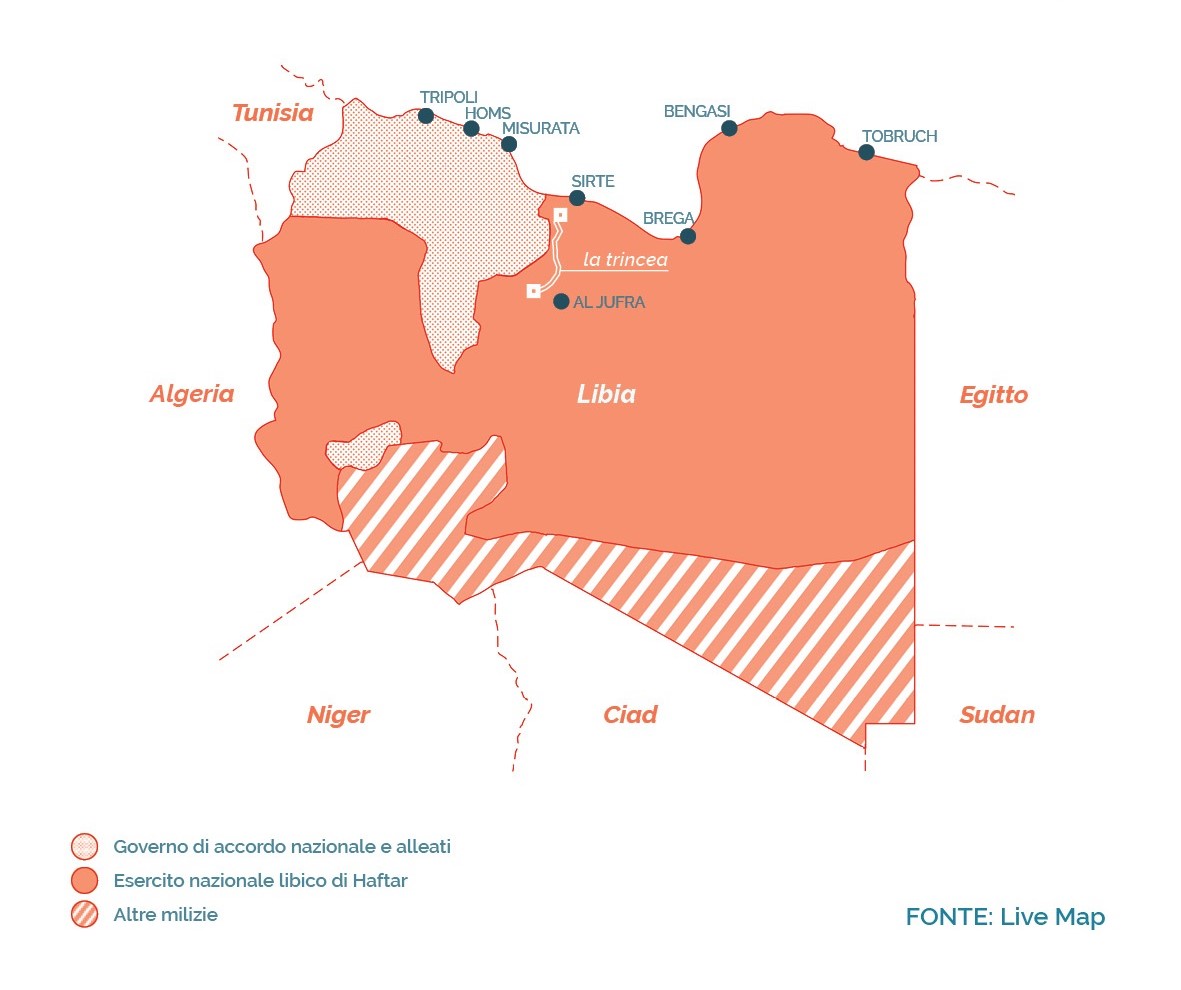

Since then, the former Italian colony is in fact a country split in two, with two parliaments opposed to each other, and has known years of civil war, also fomented, as in 2019, by the presence on the territory of foreign powers (at the beginning of December, the then United Nations envoy, Stephanie Williams, had spoken of around 20 thousand foreign forces and/or mercenaries) concerned with protecting their own interests.

A weak executive?

Despite the vote of confidence by the House of Representatives, and despite the fact that the new government has been welcomed by numerous international chancelleries and the UN mission on the spot (UNSMIL), there are still many doubts about the stabilisation of the country.

First of all, there are the accusations contained in a UN investigation according to which the new Prime Minister bribed some members of the LPDF, in order to obtain the votes needed to elect him. The accusations were immediately rejected by the Prime Minister himself, who said in a parliamentary question before the vote that he had been the victim of a smear campaign.

However, what most undermines the credibility of the new government’s ability to exercise power independently is the well-established presence of foreign powers on Libyan territory. Theoretically, both the Turks and the Russians should have withdrawn following the ultimatum scheduled for 23 January in the framework of the agreements between the two Libyan counterparts signed in Geneva under the auspices of the UN, but in practice this did not happen. Both the aforementioned actors have invested a lot in the Libyan game, and have no intention of pulling out now that they have gained a foothold in the territory.

Ankara, the main sponsor of the UN-recognised Government of National Unity (GNA), has forged increasingly close ties with the Tripolese executive: in November 2019 the parties signed a maritime agreement, while the following January 2020 Turkey intervened in support of Al Serraj to counter the advance of General Haftar, who had come to threaten the outskirts of Tripoli.

Since Turkey entered in Libya, the Haftar-led army has retreated as far as Sirte. Nowadays, pro-Turkish forces are mainly based in the naval base and port of Misrata, as well as the al-Watya air base. Erdoğan knows that the control of a part of the southern shore of the Mediterranean is a blackmail weapon against Europe regarding the migration issue and intends to use it to his advantage.

On the opposite front, Russia has also ignored the date on January the 23rd for the withdrawal of its troops; nowadays, in fact, the approximately 2000-3000 mercenaries of the Wagner company remain entrenched along the fortified defensive line of about 70 kilometres that they have erected from Sirte to the al-Jufra air base (where about 1200 Sudanese paramilitaries are stationed), which today marks the border between the territory controlled by the GNA and that controlled by the Libyan National Army (LNA). For the Kremlin’s strategy, it is essential to control bases in the North African region, thus representing a thorn in NATO’s side, threatening its southern front.

On the opposite front, Russia has also ignored the date on January the 23rd for the withdrawal of its troops; nowadays, in fact, the approximately 2000-3000 mercenaries of the Wagner company remain entrenched along the fortified defensive line of about 70 kilometres that they have erected from Sirte to the al-Jufra air base (where about 1200 Sudanese paramilitaries are stationed), which today marks the border between the territory controlled by the GNA and that controlled by the Libyan National Army (LNA). For the Kremlin’s strategy, it is essential to control bases in the North African region, thus representing a thorn in NATO’s side, threatening its southern front.

A diversified government

It is therefore clear that Ankara and Moscow have established themselves in Libya in order to remain there, and that, in order to successfully complete the internal stabilisation process, the wishes of the numerous foreign sponsors must be taken into account (in addition to those already mentioned, there are Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, France and, indirectly, Sudan and Qatar).

In this regard, it should be recalled that Ddeibah has already declared that the maritime agreement with Turkey of November 2019 should remain in force. Moreover, on the Libyan dossier, Ankara and Cairo have recently shown their intention to mitigate their positions, demonstrated in practice by the opening of the Egyptian Embassy in Tripoli.

As pointed out, the new executive is not as modest in size as hoped for by various international institutional actors, due to the fact that it has to balance internal factions and external actors that have a voice in the affair. Despite the fact that the tandem most quoted in the pre-voting forecasts, that of Aguila Saleh and Fathi Bashagha, was not chosen by the 75 delegates present at the LPDF, the two remain the main political referents of the new government of national unity (the first is Egypt’s reference man in Libya, the second a pro-Turkish exponent of the government in Tripoli). Another key figure could be Khaled Tijani Mazen, the new Minister of the Interior: originally from Fezzan, a region too often forgotten in the news, but which in reality plays an extremely important role as the crossroads of numerous migratory routes that start from the Sahel, and a man with important connections in Italy.

The objective of the new executive is to lead the country to the elections on 24 December, but in addition to this and to the challenges on the ground, there are also others of a legislative nature: the amendment of the Constitutional Charter to reduce the number of members of the Presidential Council from nine to three, and the approval of new rules on electoral law.

The situation continues to be extremely precarious, considering that the country has been torn apart by a civil war that has lasted for years, but it is fair to say that, for a few days now, a glimmer of hope has been lit in Libya.